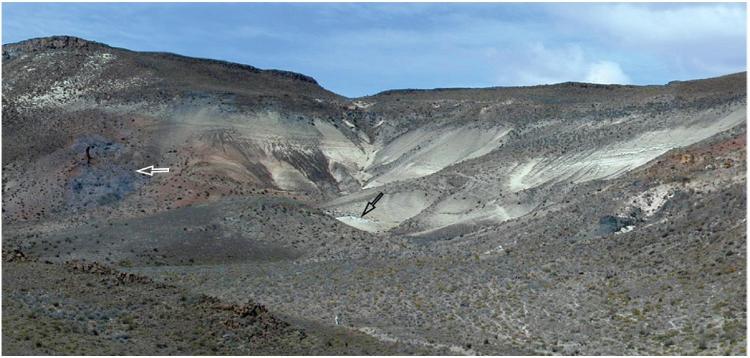

Mammal fossils lured paleontologists to Oligocene age rocks in Patagonia of Chubut Province, Argentina. The deposits pictured here were discovered by G.G. Simpson heading the Scarritt Expedition in 1934. This photograph comes from a modern paleontological expedition revisting the area. Image credit: Vucetich et al. 2014. “A New Acaremyid Rodent (Caviomorpha, Octodontoidea) from Scarritt Pocket, Deseadan (Late Oligocene) of Patagonia (Argentina).” Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 34 (3): 689 – 698.

In the 1930s, the reknowned American paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson (1902 – 1984) led a number of fossil hunting expeditions with the American Museum of Natural History to Patagonia in the southern end of South America. Simpson was very much interested in an assemblage of ancient mammals living in “splendid isolation” on the island continent of South America. His research centered upon these endemic radiations and their eventual fate when a narrow landmass, the Isthmus of Panama, arose at the end of the Pliocene (approximately 3 million years ago) and began the Great American Faunal Interchange. While searching for evidence from this epic story of South-meets-North, the expedition lightened their days enjoying the antics of local wildlife they adopted as camp pets.

The vast plains of Patagonia are a barren and savage waste in which man seems an interloper. Here in the far south of South America nature never smiles. . . Yet Patagonia has its own children, living in constant fear and combat, but somehow contriving to flourish and finding in this desolation a home suited to their own wild temperaments. . . .

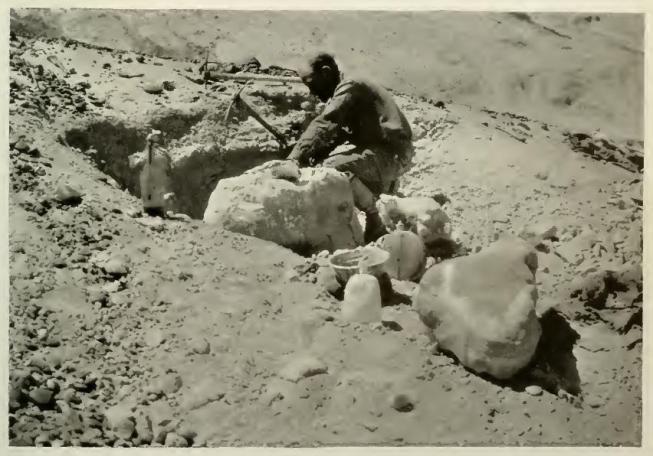

Simpson at the dig. A skeleton is carefully excavated, covered in shellac, and bandaged for safe transport. Image credit: Simpson 1932.

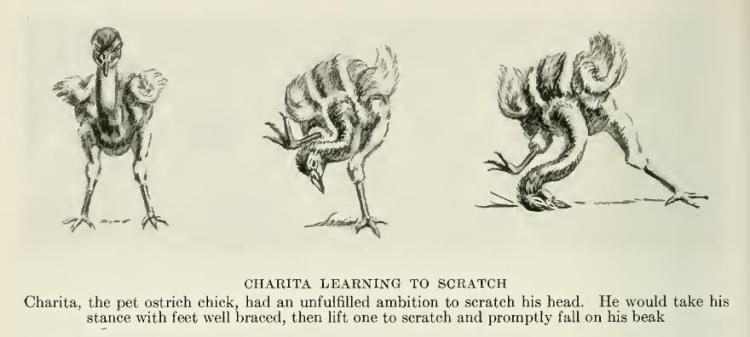

We caught one of the babies [a Darwin’s Rhea, Rhea pennata] and christened him Charita. . . . [he] soon forgot his brothers and sisters and lived with us contentedly, a silly creature with feet much too big for it, its body the size and shape of the egg from which it came (where the neck and legs fit in I do not see), covered with soft down, dark brown and striped with white like a skunk. His idea of heaven was to wedge himself tightly between two hot pans beneath the camp stove. When deprived of his sensuous pleasure, he divided his time between trying to crawl into our pockets and trying to scratch his head, laudable ambitions neither of which was ever wholly achieved. . . . He used to sleep with one of us, and soon became a real member of the family. His cry was a sad whistle, slurring down the scale and ending with a pathetic tremolo. . . . he would come running whenever we called him and would carry on long conversations with us.

Expedition members tended to name their pets after the local language — in this case, “Charita” referred to “ostrich chicks in general.” Of course, Charita was not actually an ostrich, but a related ratite indigenous to South America known as a rhea. Drawing by E.S. Lewis. Image credit: Simpson 1932.

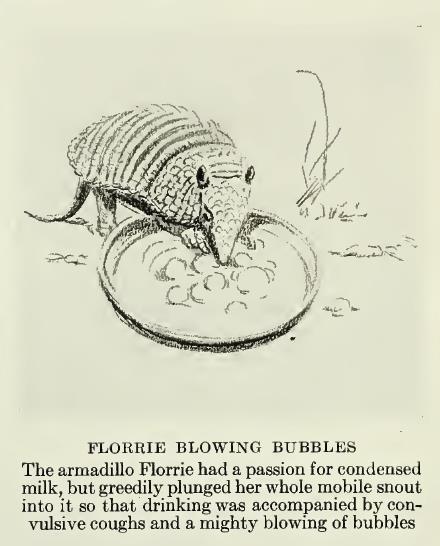

Our long favorite was a pichi [i.e., armadillo] named Florrie. . . . She came to tolerate us as servitors but never displayed any demonstrative affection. One can no more pet an armadillo than one can pet an egg or, more aptly, a tortoise, and her own attitude was always one of vapid selfishness. Yet she fully earned her keep. As she wallowed in a saucer of condensed milk we laughed more at than with her. She never learned to lap it up cleanly with her long tongue, but must always get her sharp, flexible snout in it too, so that attempts to breathe resulted in convulsive coughs and mighty blowing of bubbles. She would start to wander off, then suddenly remember the milk, dash back to it in the most business-like way and start drinking again, only to lose interest, wander off again, and repeat the whole process several times.

There was always something vague about Florrie. Her thick skin seemed to be an index to her mentality and emotions. Almost the only real emotion she betrayed was when first captured. Then, if touched, she would suddenly jump, at the same time emitting a convulsive wheeze, a maneuver as disconcerting as the explosion of a mild cigar. Later she ceased to bother. If she wandered off when let out, it was rather from absent-mindedness than from any active dislike for our society. She seemed to think with her nose, and when thus let out for exercise she would trot busily from bush to bush, poking her nose into the ground beneath and sniffing violently. Once she got away altogether and for several days we mourned her for lost, when one morning she wandered back into camp with her usual air of preoccupation. The cook, whose special friend she was, swore that she returned for love of us, and another said she had returned for free meals, but I maintain that she had simply forgotten that the camp was there two minutes after she left it, and stumbled on it again quite by accident in the course of one of her sniffing parties.

Drawing by E.S. Lewis. Image credit: Simpson 1932.

These erstwhile pets shared in the daily life of the expedition. What, if anything, was planned for their ultimate fate is a bit more ambiguous. Simpson devotes a great deal of space in this popular account to the culinary merits of the local wildlife (a hallowed tradition in scientific expeditions) and both rheas and armadillos were eaten regularly. Whether the men planned to abandon the animals, eat them, take them back to New York, or have them prepared as museum specimens, that decision soon became moot. For “. . . .Charita met an untimely end. He developed an unwholesome appetite for kerosene and, one day, finding a whole pan of this delightful beverage unguarded, he overindulged. All afternoon, he wandered about vaguely as if something was very much on his mind, or stomach, and next morning he was dead.” Likewise, Florrie, who was a cheerful presence in camp for several months, ended up being accidentally crushed to death. Despite these unhappy ends, it is clear that the hapless bumblings of animals like Charita and Florrie were the focus of much entertainment and affection during the long months of isolation grueling in the field.

Quotation Source

Simpson, George Gaylord. 1932. “Children of Patagonia.” Natural History 32 (2): 135 – 147.