Blackened leaves and Casuarina sp. cones from a controlled hazard reduction burn in Toohey Forest, Brisbane, Queensland.

It’s been a long while, fellow snurflers. Instead of the return to the blog I had been planning, I am disgorging my heart.

The horrifying images and anguished cries from the Australian bushfire crisis have traveled around the world. Maybe it’s even old news by now.

So many of you have responded generously with donations of time, compassion, and money. And things seem to be looking up. Desperately-needed rain has fallen on parched land and have even put out some fires in New South Wales. Photos of new leaves growing out of blackened landscapes offer hope of renewal.

The story does not end there. This is not a happy ending.

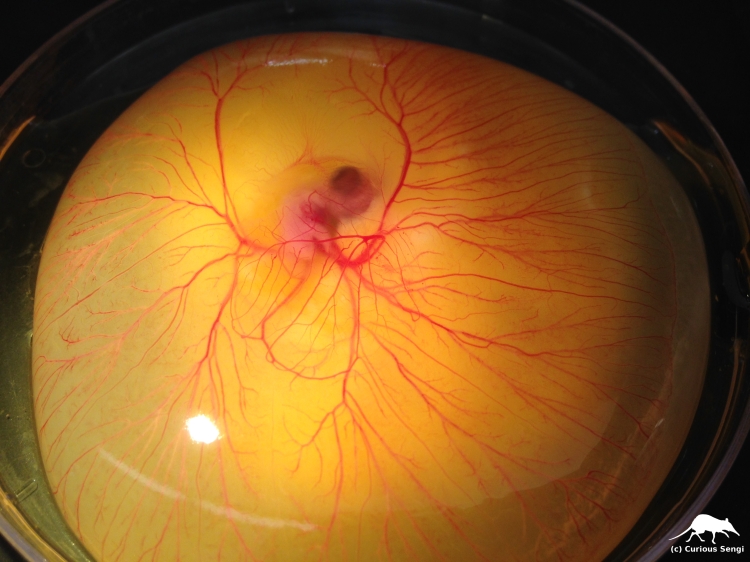

Many catastrophic fires continue to burn and Australia is still months away from the end of fire season. A conservative estimate for the number of birds, reptiles, and land-bound mammals killed by the fires is 1 billion. This estimate does not even cover the uncounted multitudes of bats, frogs, or insects. The current population of the United States is about 329 million, hardly a third of all those lives burnt to ash.

The native animals that did survive the flames are now faced with nowhere to live and nothing to eat. We can certainly anticipate that 1 billion death toll to climb higher. But we can only vaguely anticipate all the knock-on effects in the months and years ahead. The path before us may not necessarily be one of complete recovery. We may have to accept that some species are going extinct and ecosystems permanently destroyed. We may have to help our fellow humans suffer through irreparable damage done to their physical and mental health. We may have to watch as communities fail to rebuild in the face of lost loved ones, continued economic exploitation by predatory politicians and corporations, and general human apathy.

We must do our utmost not to forget what is happening here. Please continue to donate to many worthy national and local organizations (a few suggestions here). Please try to support fire-ravaged communities with your tourist dollars. Ask your Aussie mates if they are doing OK.

Most importantly, what we as a global community must do is understand that what is happening to Australia is not normal. Bushfires happen. But bushfires of this scale and intensity, compounded by high temperatures and multiple-year droughts is abnormal. This is caused by climate change. Climate change that is caused by human activity and accelerated by lack of political will, sometimes even gleeful, perverse acts of contrarianism in the face of the changes we can all see happening for ourselves.

This is not about winning or losing based on our polarized political identities. We cannot afford to think in such binary terms when we all have bodies that can burn, die of thirst and hunger, get smothered in floodwaters.

The world-as-we-know-it is as mortal as ourselves. The fossil record shows us that the Earth has experienced multiple apocalyptic events. The mass extinction of our current Anthropocene age will neither obliterate the physical Earth nor extinguish all life. But our world will end. And it will end because of our moral shortcomings. It could likely end up becoming Planet of the Garbage Rats. And we won’t even be around to welcome the new overlords.

Of course, this is not what I hope will happen. We want the things we love to live on and prosper. We want our human legacy to be one of “we were here and look at all the great things we accomplished.” We can actually do something about this.

Let’s do our best to make small changes every day towards using less resources. Let’s do our best to find common ground and not shame others who may have been misled by bad information. Let’s do our best to evaluate our sources of information and understand that some popular for-profit news outlets operate with an agenda. Let’s do our best to switch our political attention from mere personalities to the policies that are going to aggressively tackle climate change. Let’s do our best to make our voices heard, whether that is protesting or helping a conservation organization or voting with your dollar.

I am so sorry Australia, that you had to suffer so much. Even more so because during the past few years, I had the privilege of visiting twice. And I am in love with the beauty of your sublime landscapes, the utter charm of your unique native animals and plants, and the warmth of your people. You helped to heal my spirit during a difficult time. I will do my best to make sure that this bushfire crisis, this blaze seen around the world, becomes the spark that lights a beacon signal towards positive change and not a funeral pyre.

In the words of a local Aussie hero, “You look after your mates and your mates will always look after you.”