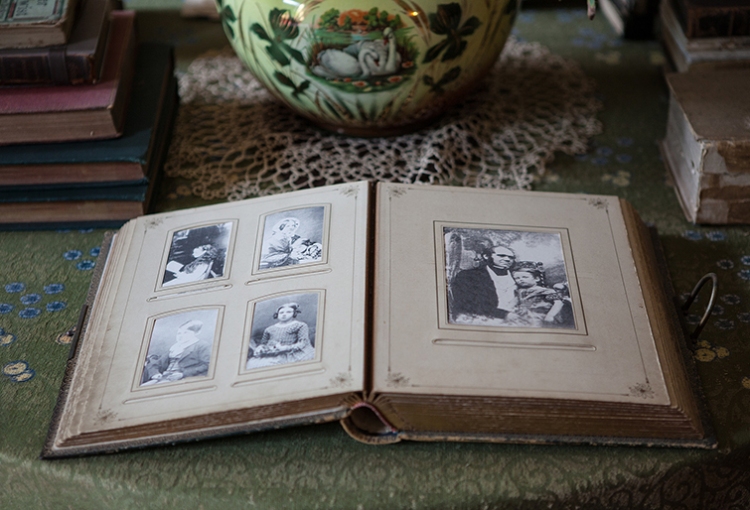

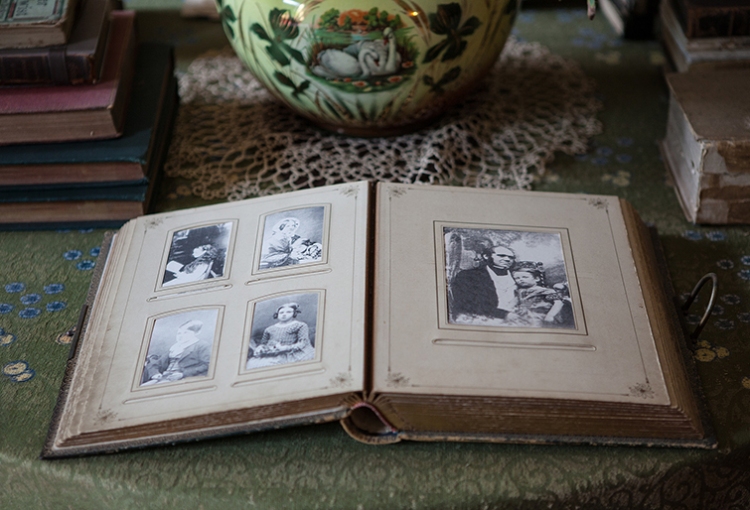

Not a birthday album, but an album of family pictures on display at Darwin’s Down House estate. Image credit: English Heritage Blog.

The celebration of Charles Darwin’s birthday (aka Darwin Day) has become an international event in recent years. But how did people celebrate Darwin’s birthday during his lifetime?

When Darwin turned sixty-eight years old in 1877, he received two large parcels in the mail. One was from Germany, a luxuriously-bound album containing the photographs and signatures of 154 German scientists and naturalists. The second parcel was another photographic album of admirers, this time from the Netherlands (Darwin 1877; Browne 2002). Darwin wrote back graciously to Professor A. van Bemmelen, who organized the effort:

SIR,—I received yesterday the magnificent present of the album, together with your letter. I hope that you will endeavour to find some means to express to the two hundred and seventeen distinguished observers and lovers of natural science, who have sent me their photographs, my gratitude for their extreme kindness. I feel deeply gratified by this gift, and I do not think that any testimonial more honourable to me could have been imagined. I am well aware that my books could never have been written, and would not have made any impression on the public mind, had not an immense amount of material been collected by a long series of admirable observers; and it is to them that honour is chiefly due. I suppose that every worker at science occasionally feels depressed, and doubts whether what he has published has been worth the labour which it has cost him, but for the few remaining years of my life, whenever I want cheering, I will look at the portraits of my distinguished co-workers in the field of science, and remember their generous sympathy. When I die, the album will be a most precious bequest to my children. I must further express my obligation for the very interesting history contained in your letter of the progress of opinion in the Netherlands, with respect to Evolution, the whole of which is quite new to me. I must again thank all my kind friends, from my heart, for their ever-memorable testimonial, and I remain, Sir,

Your obliged and grateful servant,

CHARLES R. DARWIN

At this point in his career, Darwin had already published his major works: The Voyage of the Beagle (1839), On the Origin of Species (1859), The Descent of Man (1871), and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872). He was very much in the public eye, whether as a hero of science or as the villain set on destroying the cozy blinders of Victorian religious faith. As a man who treasured quietude and harmony, the rancor raised by his theory of evolution by natural selection was deeply distressing. I do not believe that Darwin’s letter to van Bemmelen expresses any sort of false modesty, but a true gratitude, both for kindness and the international effort necessary for advancing science. Even Darwin’s wife, Emma, wrote of the arrival of the gift from the Netherlands:

. . . .yesterday arrived a most gorgeous purple velvet & silver Dutch album of the same sort with 219 portraits — some of youths, some girls & some fat women, I suppose any one who subscribed. However it shews a v. different state of feeling about him. You wd. not get boys & fat women in England to subscribe & send him their photos as a mark of respect (quoted from Browne 2002).

An international community of scientists, naturalists, and enthusiasts have continued to commemorate Darwin’s birthday, even after his death in 1882. The Darwin Day movement began in the United States in the early 2000’s, quickly blossoming into coordinated events celebrating Darwin, evolution, and science education (Wikipedia 2016).

So let’s pick up our glasses and toast to the man, Charles Darwin!

References

Browne, Janet. 2002. Charles Darwin: The Power of Place. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

Darwin, Charles. 1887. The life and letters of Charles Darwin, including an autobiographical chapter, Volume 3. Francis Darwin, ed. London: John Murray.

Wikipedia contributors. “Darwin Day.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 26 December 2016. Accessed 12 February 2017.