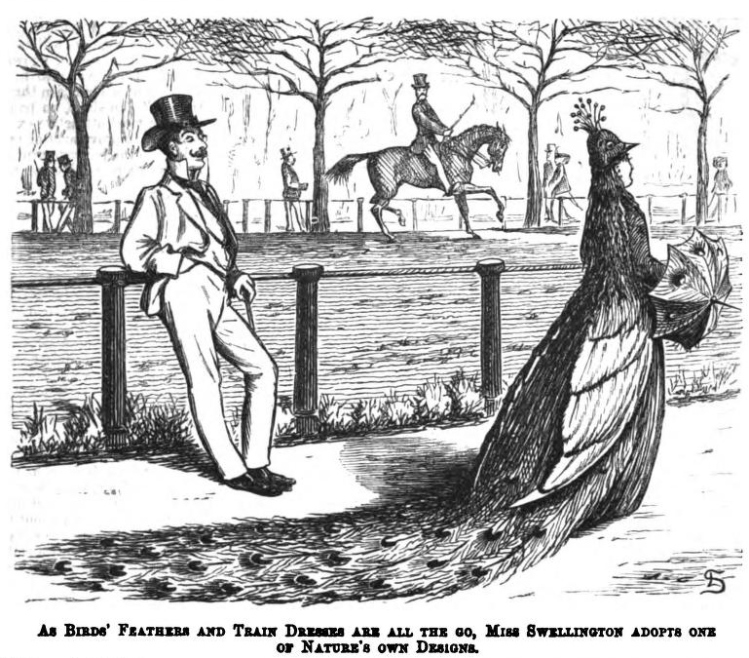

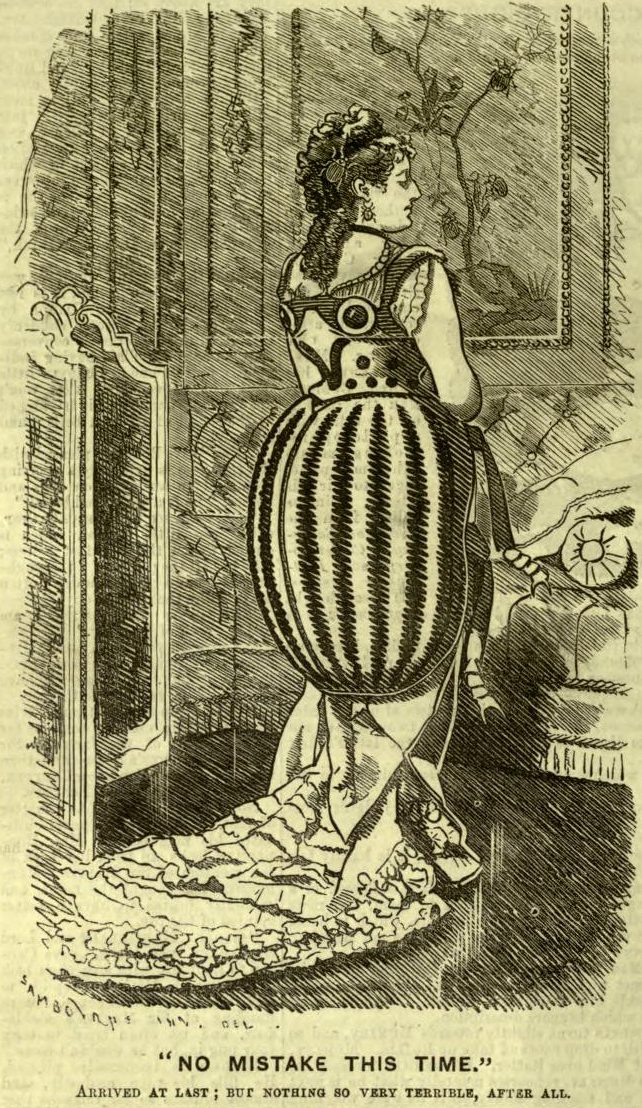

Image credit: Punch, or the London Charivari (21 December 1867).

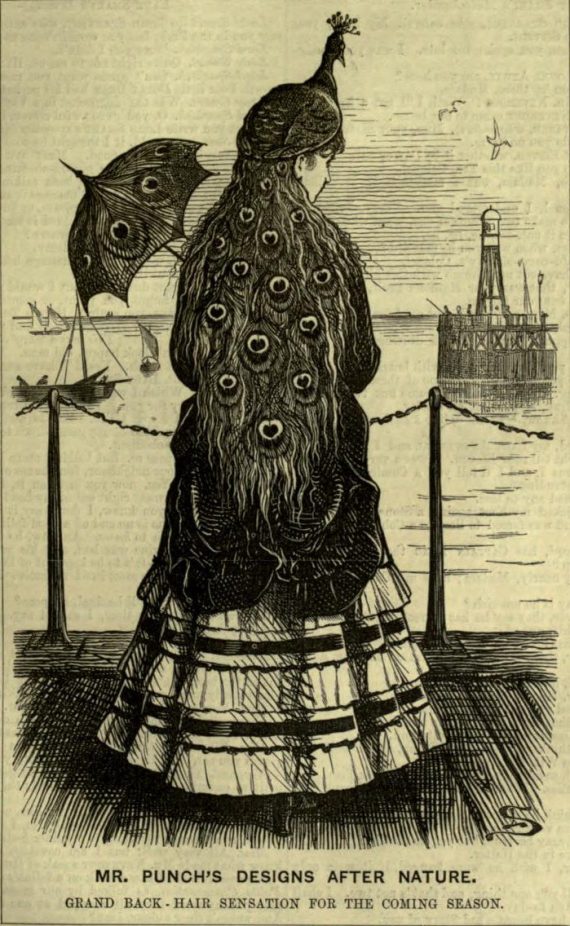

Image credit: Punch, or the London Charivari (1 April 1871).

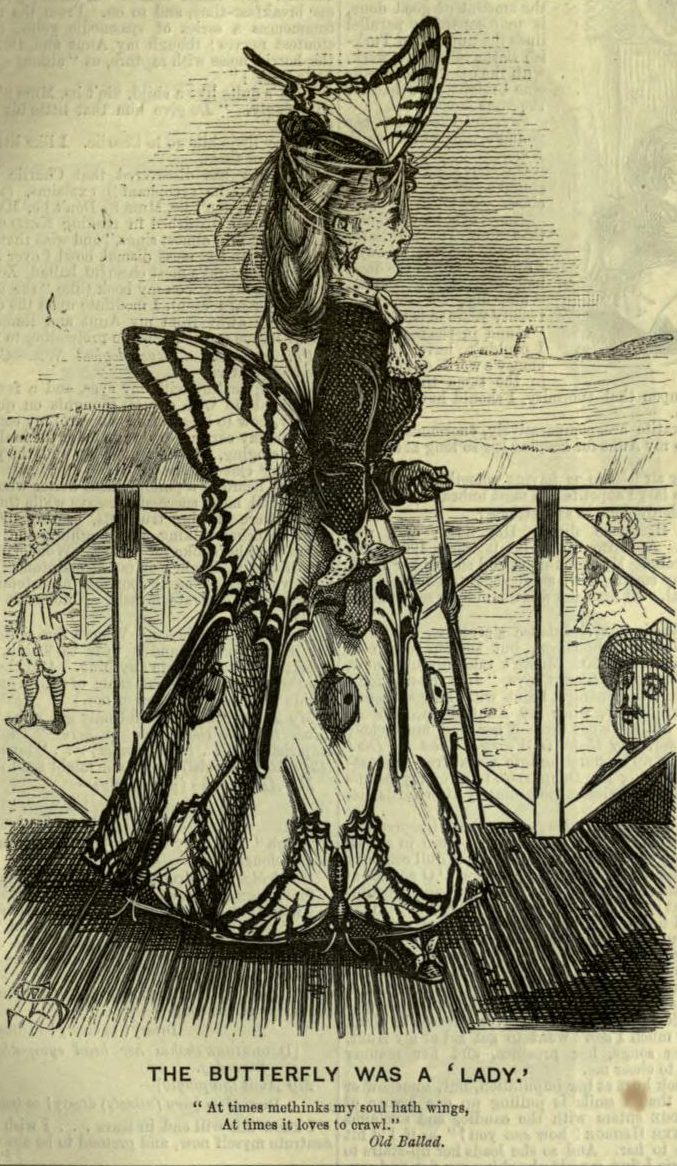

Image credit: Punch, or the London Charivari (23 April 1870).

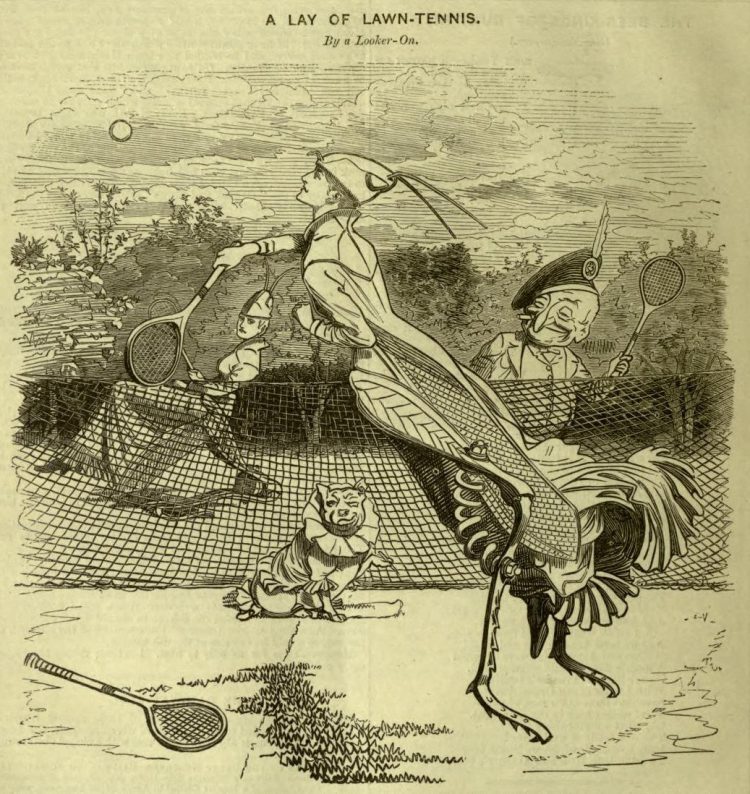

Image credit: Punch, or the London Charivari (12 October 1867).

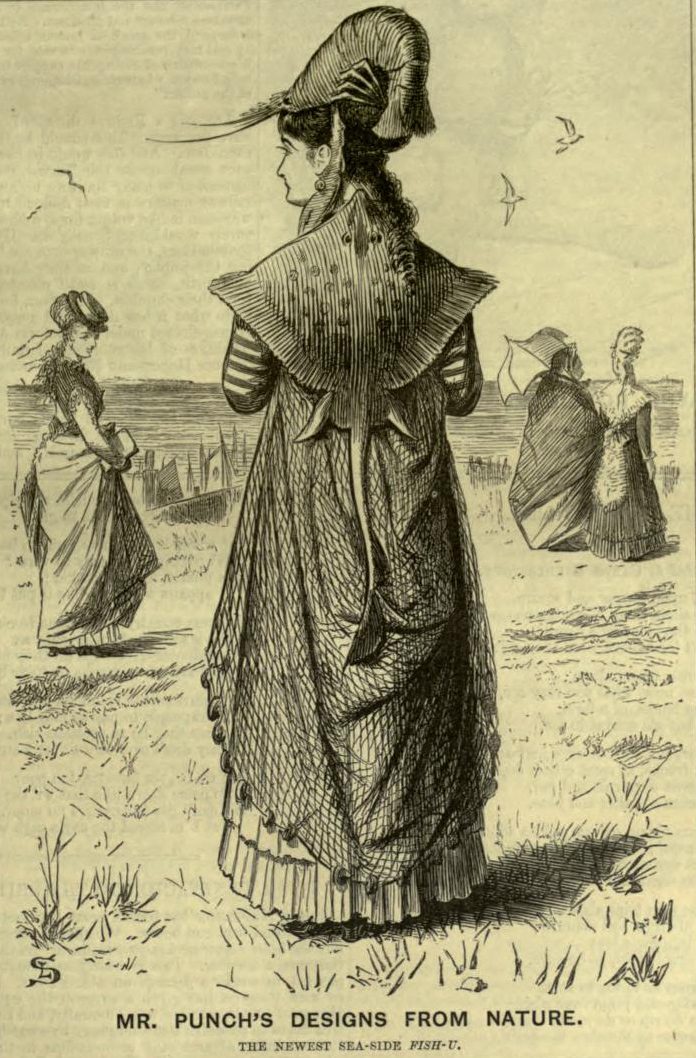

Image credit: Punch, or the London Charivari (17 June 1871).

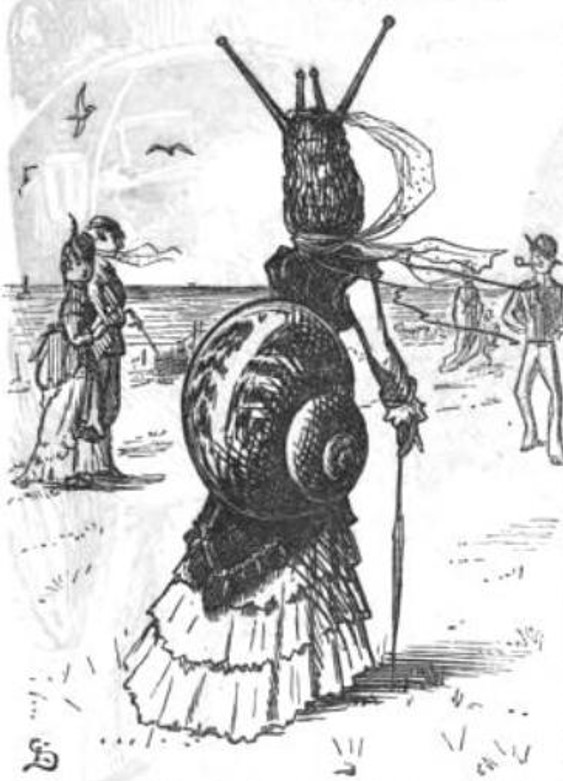

Image credit: Punch, or the London Charivari (23 September 1876).

Image credit: Punch, or the London Charivari (29 September 1877).

Image credit: Punch, or the London Charivari (5 September 1868).

Image credit: Punch, or the London Charivari (20 August 1870).

Image credit: Punch, or the London Charivari (16 October 1869).

Image credit: Punch, or the London Charivari (30 September 1871).

About These Images

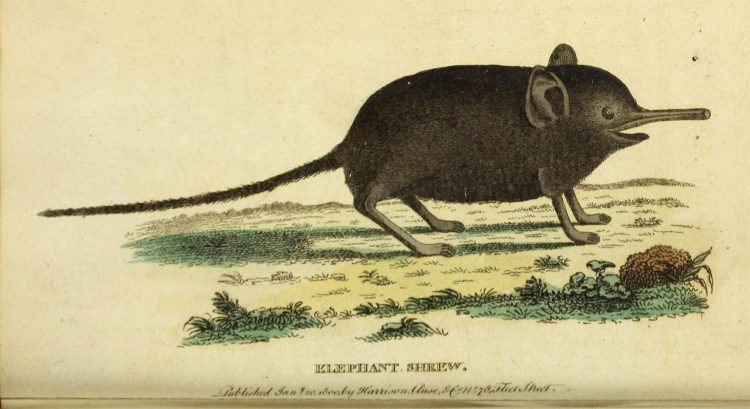

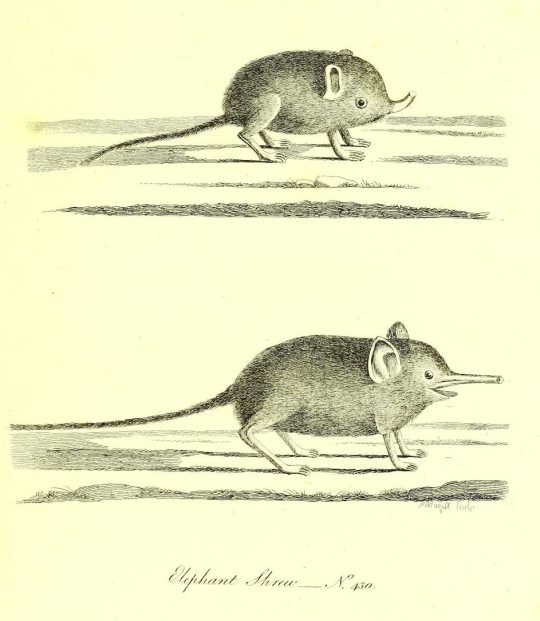

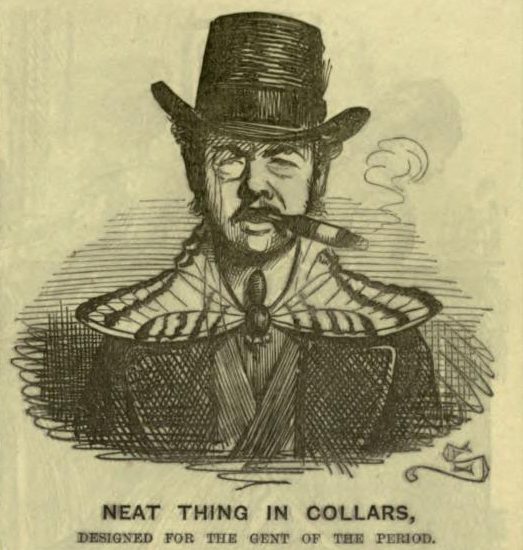

These cartoons were drawn by illustrator and photographer Edward Linley Sambourne (1844 – 1910), who worked for the popular London news and satirical magazine Punch, or the London Charivari. With the image of ‘Miss Swellington’ promenading in a peacock’s train dress, Sambourne began a series of some 20 images between 1867 and 1876 on the theme “Designs After Nature.”

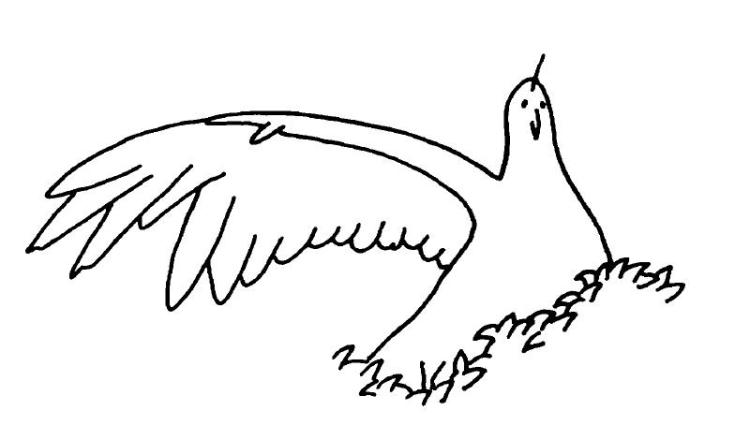

These fanciful depictions of women have drawn the attention of a few feminist scholars who have interpreted them in light of the Darwinian ideas that recently exploded in the public imagination. Bernstein (2007) sees these cartoons playing with the line separating humans from other animals, which paralleled morphing views of women in society: “. . . .an ambigously humorous angle on femininity in flux.” Likewise, the slow but steady expansion of feminine identity in the 19th century was satirized as more radical gender role reversal. Cohen (2010) identified images of women in bird plumes as perfect exemplars of Darwin’s observation in The Descent of Man that in humans, women are the more ornamental sex and they fulfill their desire for ornamentation by taking the beautiful feathers of male birds for themselves.

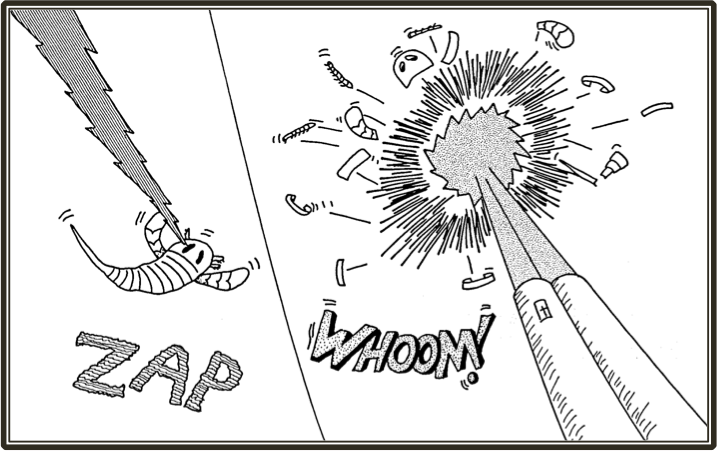

Observation and interpretation of Nature by Darwin and his contemporaries revealed a world not necessarily filled with “all things bright and beautiful.” The new Darwinian world was one of constant change, which found an apt metaphor in the fickleness of women’s fashions. Though undeniably still living under tight social constraints and blatant inequalities, Sambourne’s cartoons begin to show that women were not just the domestic angels of the Victorian household, but cunning females employing stratagems from Nature. Extravagant avian costumes are an inversion of the usual mode of sexual selection, where it is now the female competing to capture male attention and stand out amongst rivals. The prickles of a porcupine, the snail’s shell bustle, and the wasp outfit advertise the danger of tampering with a woman’s defenses. There is protective mimicry of the veiled lady masquerading as a group of butterflies. There is perhaps even unfair advantage to the woman coopting grasshopper leg mechanics in a game of lawn tennis (which is remarkably prescient of modern technological efforts to create powered exoskeleton suits).

In this parade of fashionable ladies (be sure to check back for more featured images!), biologically-inspired men’s attire is rare indeed. What we do find is the sole image of a man with a butterfly for a collar, directly facing the viewer, though his eyes are squinted with suspicion. In his gaze he is rather brutish and we sense his indifference in the unapologetic way his cigar ashes fall on the beautiful wings of the butterfly, sparing his dark, dour suit underneath.

References

Bernstein, Susan David. 2007. “Chapter 4: Designs after Nature: Evolutionary Fashions, Animals, & Gender.” In Victorian Animal Dreams: Representations of Animals in Victorian Literature and Culture. D.D. Morse & M.A. Danahay, editors. Ashgate Publishing Limited. Pp. 65 – 79.

Cohen, Claudine. 2010. “Darwin on woman.” Comptes Rendus Biologies 333 (2): 157 – 165.

Roberts, Mary Ann. 1993. “Edward Linley Sambourne (1844 – 1910).” History of Photography 17 (2): 207 – 213.