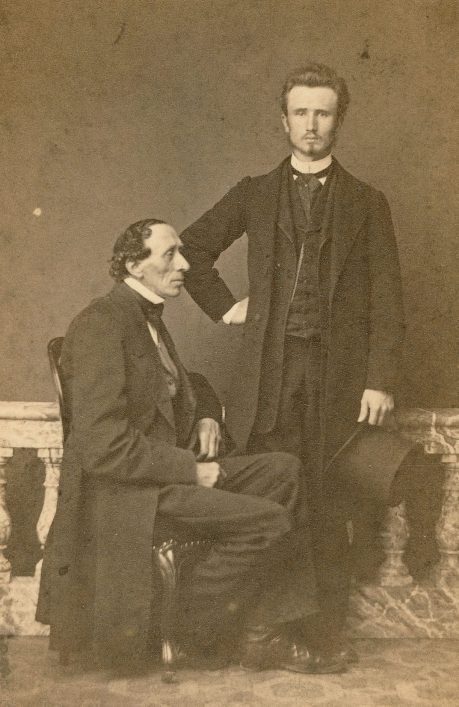

Danish author Hans Christian Andersen, who is most famous for writing beloved fairy tales such as “The Little Mermaid”, “Thumbelina”, “The Snow Queen”, “The Ugly Duckling”, and “The Emperor’s New Clothes”. Image credit: Thora Hallager via Wikipedia.

The Curious Sengi recently spent a few days in Copenhagen, snurfling about that wonderful old city. Going to visit the iconic statue of The Little Mermaid (Den lille Havfrue) was nowhere near the top of my list of things to do, but since I was already walking the ramparts of the star-shaped citadel of Kastellet, I dropped down to the harbor below to take a look. For a brief moment, I saw her: alone, looking sadly across the murmuring waves. But even the wet chill of mid-autumn did nothing to deter tour buses from roaring up the drive and disgorging scores of tourists. They gawk. They pose with big smiles and snap selfies. For a few, maybe this is the fulfillment of a dream. For others, it is just another check mark closer on the itinerary to lunch. But standing back and watching the rowdy proceedings, you cannot help but feel a bit pained. She’s such a poor little slip of a thing, caught in the moment of her greatest despair.

These daily disturbances are the least of the insults The Little Mermaid statue has endured. She has been variously decapitated, dismembered, blown up, and drenched in paint. As an easily accessible and visible tourist attraction, the statue has become the focus of protest statements and simple vandalism (Wikipedia 2016). Image credit: Curious Sengi.

Though there is a growing awareness that the fairy tales put on the big screen by Disney are intensely sugar-coated variants of the original stories that inspired them, I had to wonder how many of those tourists really knew “The Little Mermaid”, written by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen (1805 – 1875). I certainly had to refresh my memory. The story is bleak. Let’s just say that after being abandoned by the prince for whom she had sacrificed so much, the only happiness the Little Mermaid will ever experience is the release of death and the promise of an immortal soul. . . . . or disintegration into sea foam. I assume there is no noteworthy distinction there. Andersen’s story is complex, haunting, and even ambiguous. Then again, so was Andersen himself.

A vignette of Andersen’s life can be found in a small collection of shells at the Natural History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen. He began collecting local land snail shells because of Jonas Collin, the son of his close friend, Edvard. Jonas had taken up zoology and enthusiastically collected snails, an endeavor that filled their lodgings with the stink of the boiled creatures and preservative spirits when Andersen and Jonas traveled together in 1861.

Shells of land snails collected by Andersen during his travels throughout Denmark. The Natural History Museum acquired this collection in 1905. Image credit: Natural History Museum of Denmark / Curious Sengi.

During this journey, the much younger Jonas proved to be “harsh, insulting and assertive”; the constant arguments and ungrateful attitude on Collin’s part was shattering to Andersen, who confided his tearful feelings to his diary. But within this tumultuous relationship between the imperious young naturalist and the older doting author, there were moments of happiness. At the end of their travels together, the pair parted amicably and Andersen would continue poking around gardens with newly acquired interest to find more specimens to send to his friend. Andersen included this note in a letter to Jonas’ mother:

Yesterday I found a beautifully coloured snail. I thought immediately of Jonas and took it up to my room, then went to lunch; but when I went back upstairs, the snail was nowhere to be found. I searched and searched, then found the beast had crept up the back of the table. I put it in my soap dish and put a lid over it. Last night, I wanted to make my specimen, boil the snail, remove the body and keep the shell for my scientific friend, but when I came to retrieve my victim, it had disappeared again, and this time it was lost for all time. The maid had cleaned up and thrown the snail out the window, but Jonas will see that I was thinking of him, and that will appeal to him (Andersen to Henriette Collin 5 June 1862; quoted from Strager 2014).

Upon hearing the news, Jonas responded rather like a pedantic brat:

That you collect snails for me is very touching, but the fact that you let them run away again, in my opinion, balances out the praiseworthy. I would very much appreciate snails from Basnaes. You can keep them alive in a dry box with small holes in the lid. They survive for years without food by sleeping (quoted from Strager 2014).

Image credit: Natural History Museum of Denmark / Curious Sengi.

Though Andersen’s snail collecting eventually slowed to a halt (Strager 2014), he was mindful of pleasing Jonas, almost to an obsequious degree. Sometimes the young man expressed gratitude, but it can be puzzling why Andersen was so invested in this unbalanced relationship.

One possible way of understanding Andersen’s relationship with Jonas is to acknowledge the intense, and ultimately unreciprocated, feelings that Andersen had for Jonas’ father, Edvard. There can be a long discussion about whether or not Edvard Collin was once seen as a lover (Bom & Aarenstrup 2015), but it is clear enough that Andersen put both men and women at the center of his romantic and erotic attentions. In his private writings, Andersen expresses his deep yearnings, all of which seemed to end in rejection and celibacy (Bech 1998; Bom & Aarenstrup 2015).

Andersen with Jonas Collin, around the time of their snail collecting venture. Image credit: Bordeux Barberon via Wikimedia Commons.

I wonder if during his rambles with Jonas, Andersen learned that snails are hermaphrodites, capable of reproducing as both males and females, sometimes simultaneously. Andersen seems to have seen himself as androgynous (Bom & Aarenstrup 2015). Natural history would hint at a sympathetic connection between Andersen and snails — another unassuming, ugly duckling-like character that Andersen identified with. And yet he cast the snail as an egocentric curmudgeon in the story “The Snail and the Rosebush” as a jab against certain philosophers in his acquaintance (Strager 2014). No soft spot for snails there and, thus, our natural history fairy tale falls apart.

Like “The Little Mermaid”, the story of Andersen’s life was filled with much more pain and complexity than is perhaps understood. His collection of snail shells in the Natural History Museum of Denmark is but a small glimpse of that life.

Statue in Bratislava, Slovakia commemorating Andersen and some of his famous fairy tale characters, including the grumpy snail. Image credit: weepingredorger.

Read Andersen’s short story: “The Snail and the Rosebush”

References

Bech, Henning. 1998. “A Dung Beetle in Distress.” Journal of Homosexuality 35 (3-4): 139 – 161.

Bom, Anne Klara & Anya Aarenstrup. “Homosexuality.” H.C. Andersen Centret: FAQs. Syddansk University, 11 August 2015. Accessed 27 November 2016.

Strager, Hanne. 2014. Precious Things: The greatest treasures of the museum. Tam McTurk, translator. Gylling: Narayna Press.

Wikipedia contributors. “The Little Mermaid (statue).” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 24 November 2016. Accessed 27 November 2016.