This rather bedraggled looking mess is an Arctic Fox (Bering Island subspecies) beginning to shed the dark summer coat. Image credit: A. Shienok / United Nations Development Programme in Europe and CIS via Flickr.

This rather bedraggled looking mess is an Arctic Fox (Bering Island subspecies) beginning to shed the dark summer coat. Image credit: A. Shienok / United Nations Development Programme in Europe and CIS via Flickr.

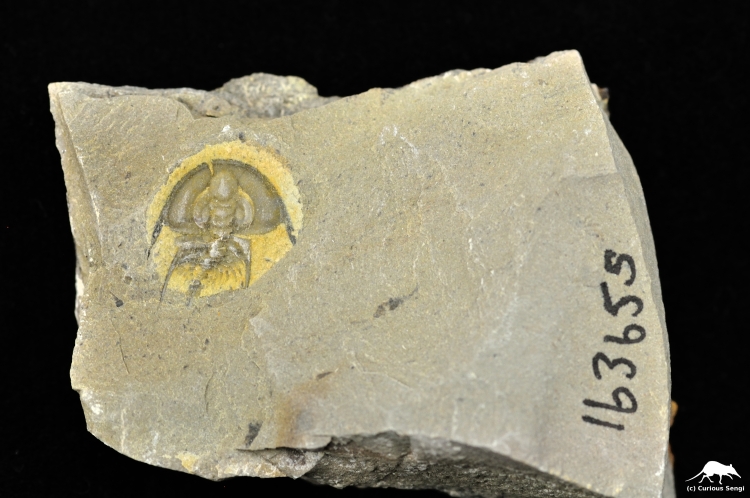

Image credit: Yale Peabody Museum / Curious Sengi.

While drifting through the Invertebrate Paleontology collections one day, I found a tray of lovely trilobites, many of them surrounded by a golden yellow halo.

Image credit: Yale Peabody Museum / Curious Sengi.

Though I do not know enough about these specimens to say what caused these halos, it is likely some kind of iron oxide stain produced by a chemical reaction between the surrounding rock material and the organic stuff oozing out of the trilobite during the fossilization process. In any case, this quirk of preservation gave these trilobites a rather ethereal glow. . . . .

Let’s have some fun with that!

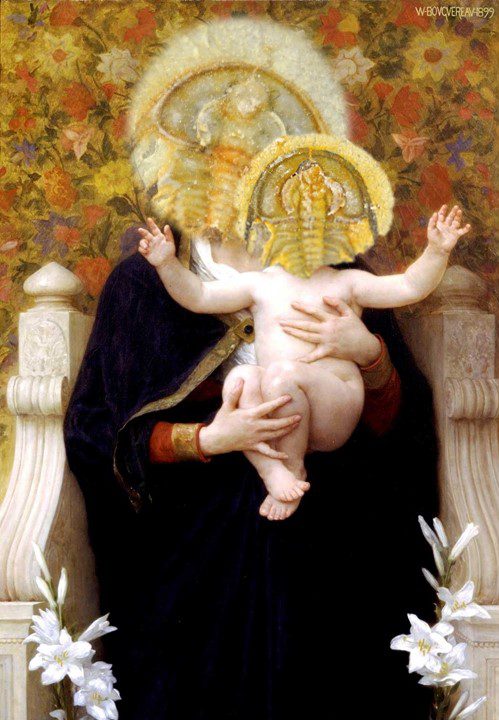

Trilobites are the ultimate Trinity. They get their name from the three lobes that divide up the main body: a central axial lobe with two pleural lobes on either side. Apologies to The Nativity of the Lower Church at Assisi by Giotto (c. 1306 – 1311). See the original fresco here.

Isn’t that better? No judgmental babies here. Just a glorious cephalon. Apologies to La Vierge au lys by Bouguereau (1899). See the original painting here.

But sometimes Nature shows you something simple and evocative. No cheap tricks and ersatz Photoshopping necessary. What do you see here? A tender “mother and child” pose? A random assemblage of bodies? One trilobite headbutting another?

Image credit: Yale Peabody Museum / Curious Sengi.

No matter how you view this image and how ever you will be celebrating this time of year, all best wishes from the Curious Sengi!

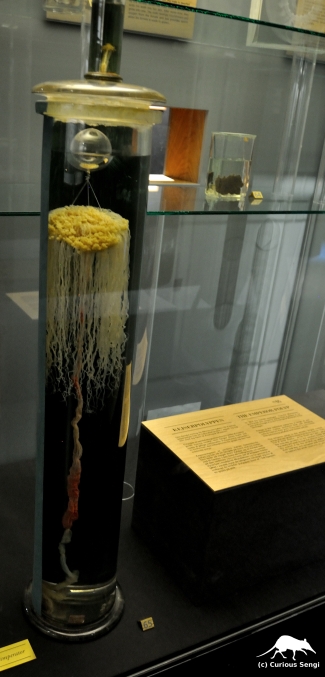

Preserved specimen of the deep sea hydroid, Branchiocerianthus imperator, is kept afloat in its jar by an air-filled glass float. Image credit: Natural History Museum of Denmark / Curious Sengi.

It was an object which was calculated to raise enthusiasm in a naturalist. A large disc surmounted a long stalk which evidently fixed the animal on the sea-bottom. A circle of numerous graceful tentacles hang down from the margin of the disc. . . . and the prevailing colour transparent scarlet (Miyajima 1900).

What Miyajima was describing is a specimen of Branchiocerianthus imperator, a solitary hydroid brought up by a long-line from a depth of over 450 meters (~1500 ft) off the coast of Japan. Hydroids are cnidarians, a group of aquatic invertebrates that use specialized stinging cells to capture prey and include more familiar creatures such as jellyfish, sea anemones, and corals. Most hydroids are small and colonial, but B. imperator is a majestic loner looming nearly a meter (~3 ft) over the deep sea plains of soft sand and mud (Miyajima 1900; Omori & Vervoort 1986).

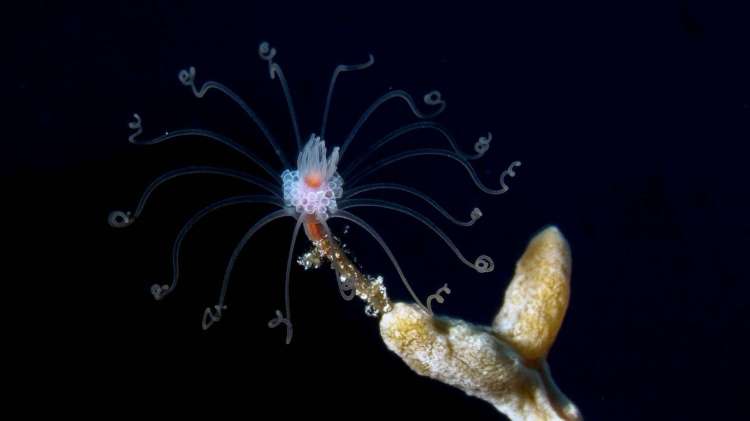

Example of a more typical solitary hydroid. This individual is likely no more than a couple of centimeters in diameter. Image credit: Dawn Clerkson via Scubaverse.com.

B. imperator as spotted by the Japanese submersible Shinkai 2000. These wonderfully strange animals consist of the hydrocaulus “stalk” and the hydranth “flower”, which bear the stinging tentacles used to capture food particles and small prey items. Miyajima also noticed that unlike many other cnidarians that have radial symmetry, B. imperator possesses bilateral symmetry (Miyajima 1900). Image credit: Oneclickwonders blog.

Delighted by the delicate reds and pinks of the animal: “It was agreed on all sides that it was a New Year’s gift from Otohime and that it should be known in Japanese as Otohime no Hangasa.” Though Miyajima was writing for a Japanese academic journal, he included a footnote to explain the origins of the moniker: “‘Otohime’ is a beautiful goddess who is supposed to have her palaces at the bottom of the sea. ‘Hanagasa’ is the flower-sun-shade or ornamental parasol. Thus Otohime no Hangasa means ‘the ornamental parasol of Otohime.’” Eager to preserve the color, Miyajima and colleagues placed the hydroid in a formalin solution, only to be disappointed as the tissues slowly bleached white (Miyajima 1900).

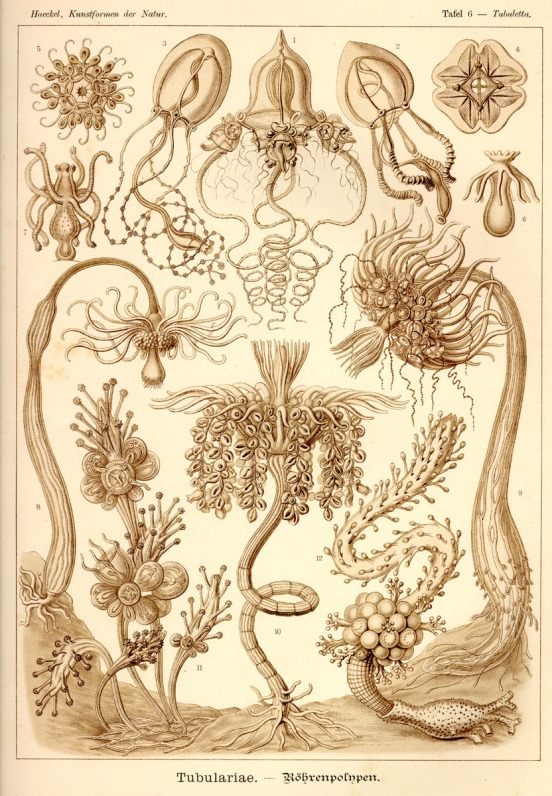

Examples of other hydroids illustrated in artistic exuberance by zoologist Ernst Haeckel. B. imperator is not represented here, but its closest relatives are the tall slender hydroids flanking either side of the plate. Omori and Vervoort (1986) described the living B. imperator as giving “. . . .the impression of the flower of a daffodil on its long stalk.” Image credit: Ernst Haeckel, “Kunstformen der Natur” (1900) via BioLib.

Despite its discovery in 1875 during the famous HMS Challenger expedition, very little is known about B. imperator. The bleached tissues and rather bedraggled look of preserved specimens have yielded important anatomical and phylogenetic data, but little else. This hydroid has been found in West Pacific waters, especially off the coast of Japan, at depths of 50 to 5307 meters (164 – 1739 ft) which make it particularly difficult to study. But brief observations of the live animal by scientists in submersibles indicate some interesting facets to the life of the largest known solitary hydroid. A juvenile myctophid fish, approximately 15 – 20 mm long, was captured by the trailing tentacles and after a 90 second struggle, was subdued by the sessile predator. In addition, tiny red shrimp were observed living symbiotically at the base of the tentacles, but their relationship with the hydroid remains a mystery (Omori & Vervoort 1986).

Buoyed by a glass float (perhaps a coincidental nod to Japanese glass fishing floats sometimes found by beachcombers) this particular specimen of B. imperator shows the whole outstretched length of the animal. Called “The Emperor Polyp” on the museum label, this item was purchased in 1914 from a dealer in Japan by Danish marine biologist Theodor Mortensen. I do not know how this individual was preserved, but some of that original rosy glow remains in the hydrocaulus, or “stalk”, of this specimen. Miyajima would undoubtedly smile at this presentation of the goddess Otohime’s flower parasol.

Image credit: Natural History Museum of Denmark / Curious Sengi.

Miyajima, M. 1900. “On a Specimen of a Gigantic Hydroid, Branchiocerianthus imperator Allman, found in the Sagami Sea.” The Journal of the College of Science, Imperial University of Tokyo 13: 235 – 262.

Omori, M. & Vervoort, W. 1986. “Observations on a Living Specimen of the Giant Hydroid Branchiocerianthus imperator.” Zoologische Mededelingen 60 (16): 257 – 261.