In celebration of Mole Day, we honor the life and research of Dr. Gillian Godfrey, who is largely remembered for her work on the life history of moles (the furry, digging kind) and writing popular books on the subject.

Gillian was described as “an extremely shy but fiercely dedicated zoologist”, who was drawn to ecology despite the “abominable lectures” given at Oxford University by Professor Charles S. Elton (1900 – 1991). After the term ended, she contacted Elton about joining his Bureau of Animal Population, but she did so with little expectation that she could have any hand in the scientific work going on there:

Her interview with Elton was awkward. He told her he didn’t care to have women in the Bureau just yet. She offered to work as a bottle washer and that did the trick. There wasn’t much future in bottle washing he retorted, so she had better come and do research (Crowcroft 1991).

Attitudes towards women in science in the 1950s was, at best, greeted with amusement or skepticism, but Gillian joined a group investigating vole (Microtus spp.) biology and pursued an ambitious research project on the “factors affecting the survival, movements, and intraspecific relations during early life” in vole populations (do not worry, the moles will come later).

Vole (Microtus spp.) Image credit: David Chapman via Saga Magazine.

The first step in this project was to induce the voles to nest so she could reliably return to her study subjects and trace their life histories.

With great single-mindedness, and almost no experience with hand tools, she set about mass producing nest boxes in D.K.’s [technician Denys Kempson’s] workshop. After his initial consternation, not because of the possibility of her injuring herself, but because he feared she might damage his tools, he diplomatically suggested that she work undisturbed in the field store. For many days the corridor echoed with the sounds of saw and hammer, and Gillian emerged with large numbers of wooden nest boxes with removable lids (Crowcroft 1991).

For all the work and enthusiasm poured into building nest boxes of all kinds of design, the voles were unappreciative of the effort and continued to built their own nests in clandestine locations (Crowcroft 1991). So Gillian proceeded to comb every square inch of her study site, crawling about on her hands and knees, parting the long tussock grass, finding plenty of old nests, and learning more about the private life of voles than this frustrating exercise initially promised (Crowcroft 1991; Chitty 1996). But this was no way to gather data for her project.

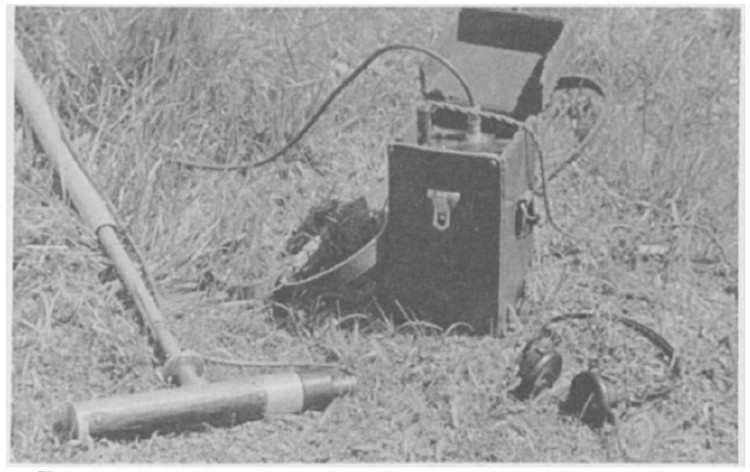

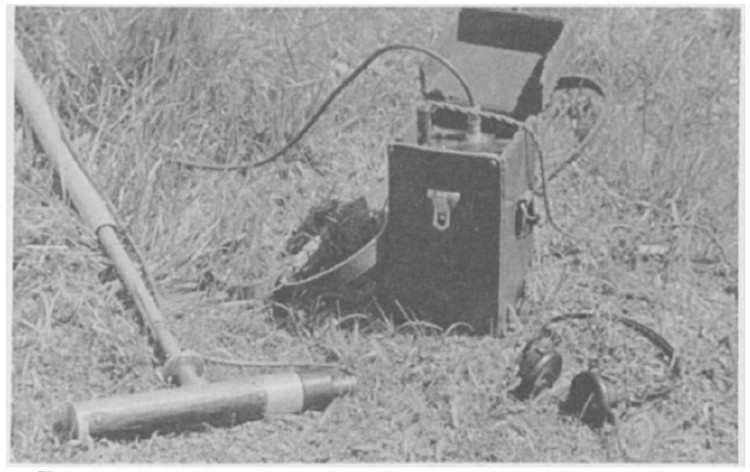

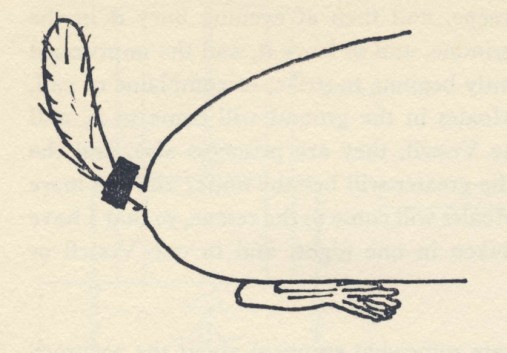

Then, in an inspired change of tactics brought about by the failure of the voles to use her nest boxes, she set out to trace their movements and find their nests by putting radioactive rings on their legs and finding them with a Geiger-Müller counter. She was greatly assisted on the technical side by a physicist with amorous ambitions which were fruitless and ill-conceived. Cobalt 60 wire was obtained. . . . before the Boss got wind of the project. He was pretty upset by her initiative, but saw that the technique had such great possibilities that she got away with it. This was the first time small mammals had been tracked in this fashion. . . . I [Crowcroft] still have some mental discomfort when I recall cutting up the wire for Gillian with two pairs of pliers, and rescuing bits that flew off by using the screaming Geiger counter (Crowcroft 1991).

The portable Geiger-counter-on-a-stick used to trace the location of voles through the thick grass. Image credit: Godfrey 1954.

It was a brilliant innovation, one Gillian claimed was inspired by the use of radioactive materials to track the movements of click beetles (Agriotes spp.) (Godfrey 1954). By mounting a Geiger counter on the end of a pole, it was possible to sweep large areas of habitat and locate an individual animal (Mellanby 1971). In writing up her novel methodology, Gillian acknowledged the advantage of this relatively non-invasive technique, since: “Nearly all available information about small wild animals has been obtained by indirect methods. . . .and it is usually impossible to assess the errors introduced. Trapping is frequently used in studies on movements but probably affects normal behaviour (Godfrey 1954).”

There were other breakthroughs to be had. Crowcroft (1991) writes:

I can recall finding Gillian in the vole room, hands streaming with blood and face streaked with tears, bravely pressing on with vole examinations, and explaining with great embarrassment, “Oh, but they bite so hard!” A few weeks later she was deftly holding them by the loose skin of the back with one hand, palpating the abdomen with the other.

One imagines that this determination and persistence carried Gillian through the tough years doing her doctorate. While composing her thesis, she was caught in the cross-currents of opposing views held by her examiners. Forced to write and re-write sections to appease these men who considered each other heretics, Gillian still navigated the conflicting torrents, and emerged triumphant. She was granted a doctorate by Oxford University in 1953 and was the first woman to complete such a degree in the Bureau of Animal Population (Crowcroft 1991; Chitty 1996).

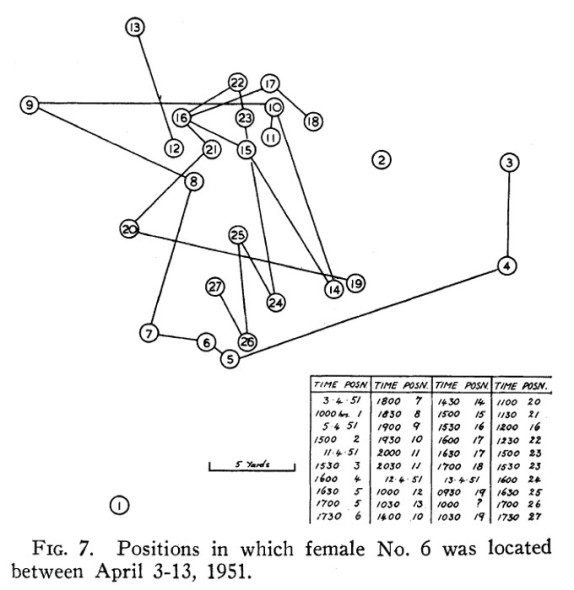

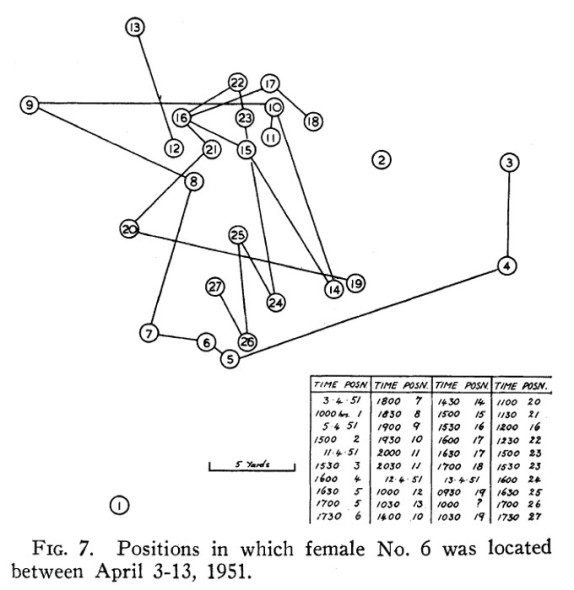

What the radioactive tracking data look like for a single vole. For this given research project, Gillian collected 709 recordings of 23 animals. These maps showed the average distance between farthest points of capture was 29.04 yards (26.6 m), encompassing an area of 235.17 square yards (215.04 square meters). Data like these provide important information on the life history and distribution of these small mammals. Image credit: Godfrey 1954.

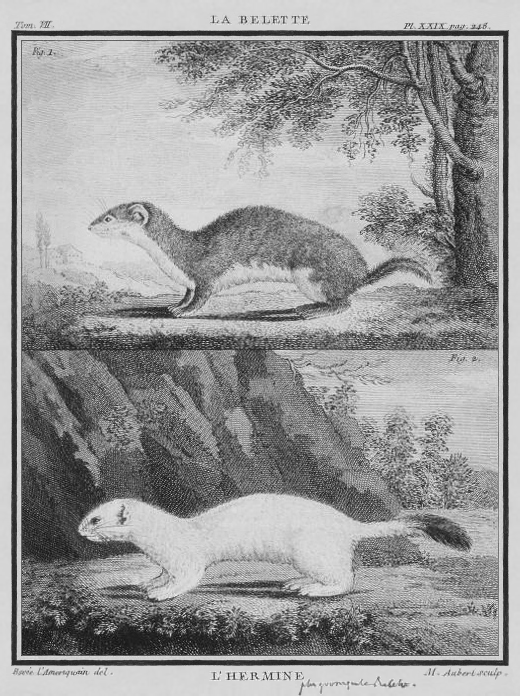

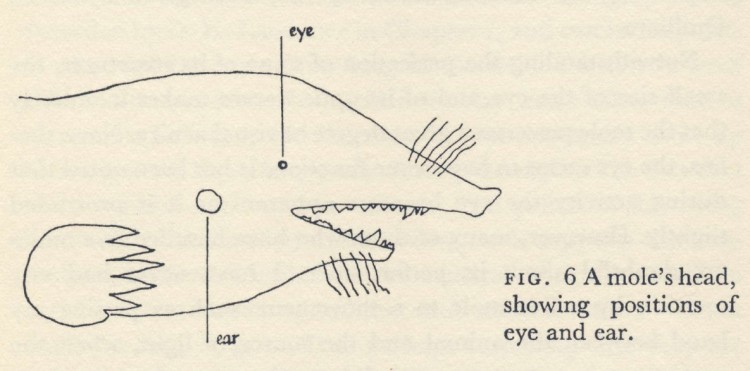

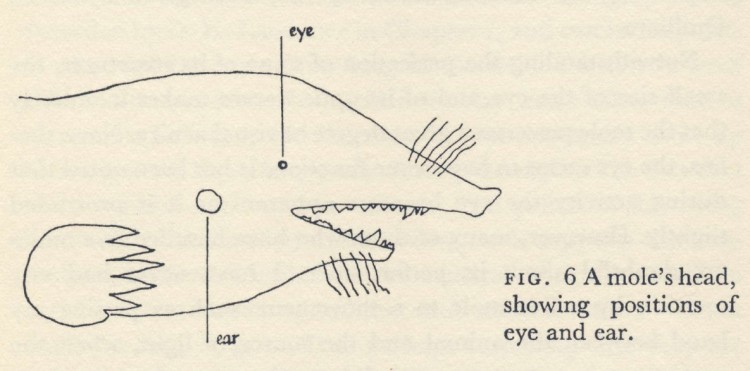

Moles are incredibly adapted to life digging underground: reduced, almost useless eyes, ears lacking any external pinnae, and powerful digging forelimbs. Since moles spend nearly all their lives underground, it had been almost impossible to reliably track their daily movements. Image credit: Mellanby 1971.

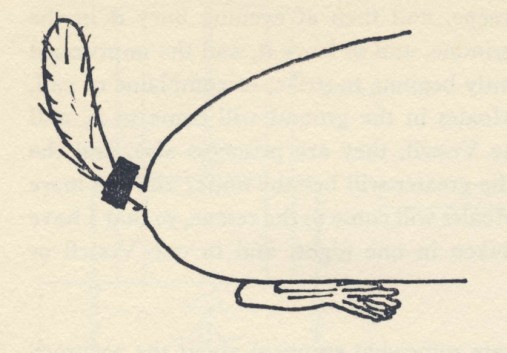

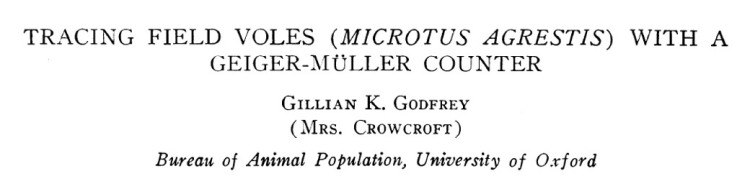

Gillian applied the same radioactive tagging technique to study the movement of moles (Talpa spp.), which are true insectivorans and not rodents like voles. This method was ideal for tracking these secretive animals. Instead of ringing the leg, a metal band with a soldered capsule containing radioactive Cobalt 60 was fixed to the mole’s conveniently club-shaped tail, which did not permit the ring to slip off when secured at the base. The ring could be detected up to 30 cm (1 ft) underground using the Geiger counter.

This drawing demonstrates the mole’s club-shaped tail: constricted at the base and widening towards the end. The black rectangle represents the position of the radioactive tracking ring. The shape of the tail prevented the ring from slipping off. Image credit: Mellanby 1971.

Even though Gillian’s tracking method became more sophisticated over the years, it was still a hazardous business to work with radioactive materials. Though she only tracked one animal at a time, she still had to be careful that the animals did not escape from the study site and leave radioactive rings strewn all over the English countryside. Of course, there was concern that prolonged exposure to Cobalt 60 would have a deleterious effect on the moles. Despite all these dangers, Gillian discovered a lot about these animals, including their reproductive habits, home range, and propensity towards three bouts of periodic activity over a 24 hour period (Mellanby 1971). In 1960, Gillian and her husband, Peter Crowcroft, a Tasmanian zoologist and zoo director (Chitty 1996), published The Life of the Mole, which received both academic and popular praise (Kettlewell 1961).

Unfortunately, Gillian Godfrey’s own trail quickly goes cold. Like many women of her time, Gillian was largely defined by her husband. She married Peter Crowcroft in 1952, while they were still students together at Oxford (Lidicker & Pucek 1997). We learn from an article in the Chicago Tribune that Peter was hired to be director of the Brookfield Zoo in 1968. At the time, Gillian was researching marsupials at the University of Adelaide, but would soon leave to join Peter in Chicago. Upon Peter’s death in 1996 at the age of 73, we read in his obituary that Gillian was, in fact, his second wife. But at the time of publication, she had disappeared from the picture and Peter was survived by another wife, Lisette.

Gillian seems to have retained her maiden name throughout her scientific career, but sometimes it was necessary to remind people to whom she was married. Image credit: Godfrey 1954.

What happened to Gillian? The answers are harder to find. Radioactive tagging is no longer used to track animal movements in the field, so it is quite likely this contributed to her work fading from scientific consciousness. But it was an ingenious solution to the problem of following shy, elusive animals in way that was least disruptive to their habits. Were there more ingenious solutions to address new questions that sparked her interest? I wish that I were able to find more information about Gillian’s later life and career, and that I could provide some kind of conclusion to this story.

So, Gillian, if you are out there, I hope you know that we think you are amazing!

Gillian out the field, listening for radioactive small mammals. Image credit: Godfrey 1954.

References

“Australian New Zoo Head at Brookfield.” Chicago Tribune. 7 February 1968: 4. Chicago Tribune. Web. Accessed 20 October 2016.

Chitty, Dennis. 1996. “Do Lemmings Commit Suicide? Beautiful Hypotheses and Ugly Facts.” New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Crowcroft, Peter. 1991. Elton’s Ecologists: A History of the Bureau of Animal Population. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Kettlewell, H.B.D. 1961. “All about the mole.” New Scientist 9 (217): 107.

Lidicker, W.Z. & Z. Pucek. 1997. “William Peter Crowcroft (1922 – 1996).” Acta Theriologica 42 (3): 343 – 349.

Mellanby, Kenneth. 1971. The Mole. New York, NY: Taplinger Publishing Company.