Painted Desert of Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona. The distant skies are filled with virgas, rain that evaporates before it reaches the ground. Image credit: Curious Sengi.

This post is part of a series commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. You can read about the first specimen to enter the Vertebrate Paleontology collection here. This story is about the most recent fossils to enter the collections — specimens that were collected just over a month ago in May and June 2016 during a field expedition to the Triassic rocks of Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona.

Our dig site is marked by a dark blue tarp, a faint pinprick of artificial color in the Painted Desert. At this point, we had already trudged over a mile through the trackless desert: picking our way between the low scrub, avoiding rattlesnakes, and using a distant red-lipped hill as our only bearing. Now we stood at the edge of badlands, where the fossils are. The heat of the day is rising. And that blue tarp is still painfully far away.

No sane human being would be out here.

The black arrow marks the location of the blue tarp that covers one of the multiple dig sites worked during the 2016 field expedition. Image credit: Curious Sengi.

In our heat-addled hallucinations, we see the dreamscape of the desert, where gypsum erupts from the red earth like misshapen white molars or glittering panes of broken glass. Millions of years of sediment deposition stand out in vivid colors, much too reminiscent of seven-layer dip and Neapolitan ice cream — trivial pleasures in an endless panorama. Fat horny toads blink their stoic welcome. Small lizards eye us suspiciously and make their challenge with jerky little push-ups before losing their nerve and diving for cover. Lanky jackrabbits flash across the hills and disappear like omens. Vampiric winds suck the moisture from our lips. Dust devils gather. When it stops, the cedar gnats come. Bone chips weathering out of a hillside metamorphose into wishful thinking with the changing light. Black zigzag lines on a pale potsherd is a startling reminder that we were not the first to venture out here. But we are here now, driven by the hope of finding ancient beasts beyond all imagining.

Colorful layered sediments. Image credit: Curious Sengi.

Native American potsherd discovered while hiking. All archaeological artifacts found in the park are photographed, given GPS coordinates, and reported to park officials. The artifacts themselves are left untouched. Image credit: Curious Sengi.

The desert is a ravishing world that simultaneously destroys and restores. For those moments of absolute beauty and discovery, we gladly welcome all the associated abuses it renders upon us. After all, we are far away from the annoyances of home and office. These are the few precious weeks out of every year we have in order to collect. Collecting fossils is, of course, always a grand adventure of luck, sharp eyes, and digging holes. But each expedition is just a beginning, the very first unfolding of multiple layers of discovery.

It starts with your eye catching something a little different, something a bit unusual and curious. Perhaps it is the color or texture or shape — even just a feeling — that draws you to a piece of bone on the ground surface. Other times, it is stunningly obvious: a tooth with glossy enamel shining on the surface of rock pulled out from a quarry. But for the most part, all you can know is that this is a fossil.

A little spot of homemade shade is a respite from a full day in the sun and wind. Image credit: Curious Sengi.

Life under the tarp. Fossil preparator Christina Lutz works on undercutting a plaster jacket. Image credit: Curious Sengi.

Big bone weathering out the side of a hill. Image credit: Curious Sengi.

Yale Peabody Museum’s chief fossil preparator, Marilyn Fox, puzzles over the big bone. After brushing away the dirt and layer of bone weathered into dust, some shapes begin to take form. Even so, the identity of the fossil remains a mystery. Image credit: Curious Sengi.

Our priority in the field is to bring fossils back safely to the museum. The care and preservation of specimens begins out there under the sun and blowing dust. A touch of archival glue might help consolidate fragile pieces together. Loose specimens are wrapped in packets of toilet paper and aluminum foil. Larger specimens or bone embedded in the matrix are given a generous buffer of surrounding rock before being encased in hard protective plaster jackets. Everything is meticulously labelled with field numbers and recorded with good locality data. Always, good locality data.

Some of the treasures brought back from the expedition. These plaster field jackets cover and stabilize fossils that remain embedded in rock. Collectors mark approximate areas where bone is located in the block. Image credit: Curious Sengi.

These bundles return to the museum, often with very little idea of what the bone is or what kind of animal it belonged to. That second moment of discovery comes when the fossils are prepared out of the rock, unveiling the extent of their shape and identity. It takes skill and patience to prepare fossils, so this moment might be delayed by months or even years. Even then, careful preparation might only reveal that an unidentifiable bone shard is just an unidentifiable bone shard. Stunning or not, all of these specimens will eventually be accessioned into museum records and properly housed to ensure their long-term preservation.

The next moments of discovery are potentially infinite. What can we learn from this specimen? What does it say about anatomy or ecology or geological processes? This moment could come from an observation waiting to be made tomorrow. It could also stretch off into the future as generations of researchers find new questions to ask and innovate better ways of extracting information. The vertebrate paleontology collections at the Yale Peabody Museum have the benefit of a long history — specimens that were discovered over a century ago have not exhausted their scientific value and are now being investigated using novel technologies, such as microCT scanning, that were beyond the wildest dreams of their original collectors.

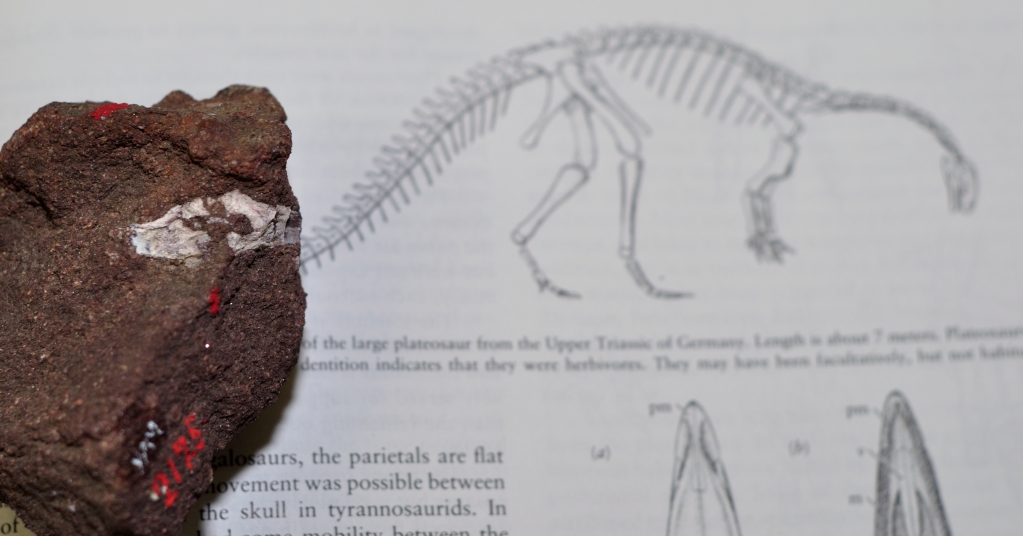

Some dig sites contained bone encrusted in an unknown material similar to oxidized iron. Preparator Christina Lutz is experimenting with chemical methods to remove this layer. Research in museums also includes discovering better ways to prepare, conserve, and preserve specimens. Image credit: Curious Sengi.

Specimens fresh from the field. Image credit: Curious Sengi.

We have now returned as collectors ourselves. Even at our desks and computers, we feel a fellowship with all those who experienced the beauty and brutality of the desert in search of fossils. We also feel a certainty that those long-dead collectors would be as grateful as we are, to know that our contributions will endure in the hands of dedicated museum staff and curious minds yet to arrive. These specimens will be here, waiting for their many moments of discovery to unfold.

And we also wait here, watching the calendar for the next time we can step out into field.

The joys of camp. Some of the field crew prepare dinner. Members of our expedition came from all backgrounds and experience levels. The team included undergraduate students, volunteers, museum professionals, and academics. Image credit: Curious Sengi.

Until next time. . . . . Image credit: Curious Sengi.

Special thanks to Marilyn Fox and Christina Lutz for their help in preparing this post.